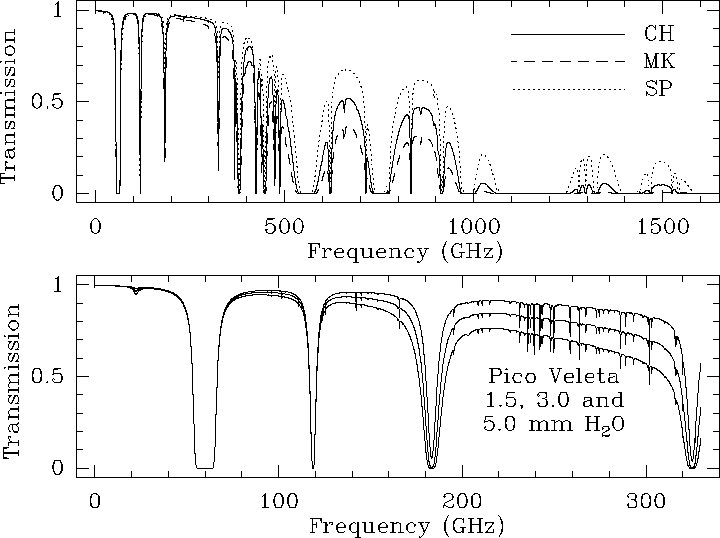

Calculations of zenith atmosphere opacity at 2.5 and 2.9 km, the

altitude of the IRAM sites, can be performed with the updated ATM

model [Pardo et al. 2001b] (see Figure 10.4). In fact, the

model itself has been installed on-line on the IRAM telescopes of

Pico Veleta and Plateau de Bure; it is activated at each

calibration or skydip and allows to interpret the observed sky

emissivity in terms of water and oxygen contributions and of upper

and lower sideband opacities. Note that the opacities derived from

sky emissivity observations do not always agree with those

calculated from the measurement of ![]() and the relative

humidity on the site, as water vapor is not at hydrostatic

equilibrium.

and the relative

humidity on the site, as water vapor is not at hydrostatic

equilibrium.

The typical zenith atmospheric opacities, in the dips of the 1.3 mm and 0.8 mm

windows (e.g. at the frequencies of the ![]() and

and ![]() rotational transitions of

CO, 230.54 and 345.80 GHz ), are respectively 0.15-0.2 and 0.5-0.7 in winter at the

IRAM sites. The

astronomical signals at these frequencies are attenuated by factors of respectively

rotational transitions of

CO, 230.54 and 345.80 GHz ), are respectively 0.15-0.2 and 0.5-0.7 in winter at the

IRAM sites. The

astronomical signals at these frequencies are attenuated by factors of respectively

![]() and 2 at zenith, 1.3 and 2.8 at 45 degree elevation, and 1.7 and 6 at

20 degree elevation. Larger attenuations are the rule in summer and in winter by

less favorable conditions. The

and 2 at zenith, 1.3 and 2.8 at 45 degree elevation, and 1.7 and 6 at

20 degree elevation. Larger attenuations are the rule in summer and in winter by

less favorable conditions. The ![]() line of CO, at 115.27 GHz, is close

to the 118.75 GHz oxygen line.

Although this latter is relatively narrow, it raises by

line of CO, at 115.27 GHz, is close

to the 118.75 GHz oxygen line.

Although this latter is relatively narrow, it raises by ![]() 0.3 the atmosphere

opacity (which is 0.35-0.4). The atmosphere attenuation is then intermediate

between those at 230 and 345 GHz (by dry weather, however, it is more stable than

the latter, since the water contribution is small). The measurement of accurate CO

line intensity ratios (even not considering the problems linked to differences in

beam size and receiver sideband gain ratios) requires therefore good weather, a high

source elevation, and a careful monitoring of the atmosphere.

0.3 the atmosphere

opacity (which is 0.35-0.4). The atmosphere attenuation is then intermediate

between those at 230 and 345 GHz (by dry weather, however, it is more stable than

the latter, since the water contribution is small). The measurement of accurate CO

line intensity ratios (even not considering the problems linked to differences in

beam size and receiver sideband gain ratios) requires therefore good weather, a high

source elevation, and a careful monitoring of the atmosphere.

During the past few years, new ground-based astronomical observatories have been built to allow access to the submillimeter range of the electromagnetic spectrum. Potential sites are now being tested for more ambitious instruments such as the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA). All of these are remote, high altitude sites. For our simulations we have selected three sites of interest for submillimeter astronomy: Mauna Kea, HI, USA (LAT=19:46:36, LONG=-155:28:18; home of the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory, James Clerk Maxwell Telescope and Submillimeter Array), Chajnantor, Chile (LAT=-23:06, LONG=-67:27; site selected for ALMA) and the Geographic South Pole (site of the Antarctic Submillimeter Telescope and Remote Observatory). The results of this comparison are also shown on Figure 10.4.

|

By analogy with the Rayleigh-Jeans approximation,

![]() , which strictly

applies to long wavelengths, the mm-wave radio astronomers have introduced the

concept of ``radiation'' or ``effective'' temperatures, which scale linearly

with the detected power.

, which strictly

applies to long wavelengths, the mm-wave radio astronomers have introduced the

concept of ``radiation'' or ``effective'' temperatures, which scale linearly

with the detected power.

The noise power detected by the telescope is the sum of the power received by the

antenna,

![]() , and of the noise generated by the receiver and

transmission lines,

, and of the noise generated by the receiver and

transmission lines,

![]() .

.

Using Nyquist's relation

![]() ,

,

![]() and

and

![]() can be expressed in terms of the temperatures

can be expressed in terms of the temperatures ![]() and

and

![]() of two resistors, located at the end of the transmission line, which would

yield noise powers equal to

of two resistors, located at the end of the transmission line, which would

yield noise powers equal to

![]() and

and

![]() ,

respectively:

,

respectively:

![]() .

.

![]() is called the ``antenna temperature'' and

is called the ``antenna temperature'' and ![]() the ``receiver

temperature''.

the ``receiver

temperature''. ![]() becomes

becomes ![]() when the receiver horn sees a load, instead

of the antenna, and

when the receiver horn sees a load, instead

of the antenna, and ![]() when it sees the ground. It should be noted that

when it sees the ground. It should be noted that

![]() and

and ![]() are not stricto sensus equal to the load and ground physical

temperatures, but are only ``Rayleigh-Jeans'' equivalent of these temperatures (they

are proportional to the radiated power). For ambient loads, they approach

closely the physical temperature, since

are not stricto sensus equal to the load and ground physical

temperatures, but are only ``Rayleigh-Jeans'' equivalent of these temperatures (they

are proportional to the radiated power). For ambient loads, they approach

closely the physical temperature, since

![]() K at

K at

![]() mm.

mm.

When observing with the antenna a source and an adjacent

emission-free reference field, one sees a change

![]() in antenna temperature. Because of the

calibration method explained below, it is customary, in mm-wave

astronomy, to replace

in antenna temperature. Because of the

calibration method explained below, it is customary, in mm-wave

astronomy, to replace

![]() , the source antenna

temperature, by

, the source antenna

temperature, by

![]() , the source antenna temperature

corrected for atmosphere absorption and spillover losses. Both are

related through:

, the source antenna temperature

corrected for atmosphere absorption and spillover losses. Both are

related through:

![]() , where

, where ![]() is the line-of-sight

atmosphere opacity.

is the line-of-sight

atmosphere opacity. ![]() is the forward efficiency factor,

which denotes the fraction of the power radiated by the antenna on

the sky (typically of the order of 0.9, see also Chapter

1).

is the forward efficiency factor,

which denotes the fraction of the power radiated by the antenna on

the sky (typically of the order of 0.9, see also Chapter

1).

The source equivalent ``radiation temperature'' ![]() (often improperly called

``brightness temperature'' and therefore denoted

(often improperly called

``brightness temperature'' and therefore denoted ![]() when it is averaged over

the main beam) and

when it is averaged over

the main beam) and

![]() are related through

are related through

where

![]() is the antenna power pattern.

For a source smaller than the main beam,

is the antenna power pattern.

For a source smaller than the main beam,

![]() (where

(where ![]() is the beam efficiency

factor, see also Chapter 1).

is the beam efficiency

factor, see also Chapter 1).

When observing a small astronomical source with temperature

![]() K, located at an elevation

K, located at an elevation ![]() , one

detects a signal

, one

detects a signal

![]() (of scale:

(of scale: ![]() volt or

counts per Kelvin):

volt or

counts per Kelvin):

This signal can be compared with the signals observed on the blank

sky (![]() ), close to the source, and to that observed on a hot load

(

), close to the source, and to that observed on a hot load

(![]() ):

):

Let's assume that

![]() ;

then:

;

then:

Typically, the mean atmosphere temperature is lower than the ambient temperature

near the ground by about 40 K:

![]() ; then, the

formula above still holds if we replace

; then, the

formula above still holds if we replace ![]() by:

by:

The receiver is not purely single-sideband. Let us denote by ![]() and

and ![]() the

normalized gains in the receiver lower and upper sidebands,

the

normalized gains in the receiver lower and upper sidebands,

![]() . The

atmosphere opacity per km varies with altitude as does the air temperature.

. The

atmosphere opacity per km varies with altitude as does the air temperature.

Then, the above expressions of ![]() and

and ![]() should be explicited for each

sideband (

should be explicited for each

sideband (![]() or

or ![]() ):

):